Volha Vialichka, psychologist

1. “It’s your own fault that you ended up there.”

Such words devalue the pain and suffering of a person who may already carry a heavy burden of guilt.

Example: one woman who was imprisoned “for extremism” simply for forwarding a photo heard after her release: “Well, you shouldn’t have gotten involved in politics.” This prevented her from seeking support and increased her sense of isolation.

2. “At least they fed you there, right?”

At first glance, it may seem like harmless curiosity. But for someone who endured hunger, poor-quality food, or forced refusal to eat due to stress, this question is painful and humiliating.

Example: a man imprisoned for “protests” said the prison food caused constant stomach problems. When people joked, “Well, at least you lost weight,” it felt like mockery.

3. “The main thing is that you’re alive.”

Yes, life is valuable. But this phrase can block the opportunity to speak about pain, trauma, and losses experienced behind bars. A person may feel forced to “be happy” when internally they are not ready or cannot find meaning in it.

4. “Don’t exaggerate — everyone has problems, life outside is even harder.”

This denies the person’s unique experience and forces them into silence. For those who survived imprisonment, the feeling that their pain “doesn’t matter” deepens isolation.

Example: a woman who returned after a year in a colony heard colleagues say: “Do you think it was easy for us outside?” It made her stop wanting to share her struggles.

5. “You should be happy that you’re free now.”

Release is not the end, but the beginning of a new path: restoring health, finding work, rebuilding relationships. Constant reminders to “be happy” create pressure.

Example: a former political prisoner could not sleep due to flashbacks of prison inspections. When friends said, “You’re home now, forget it,” she felt wrong and incapable of adapting to freedom.

6. “Tell me everything in detail — what did they do to you there?”

Interest is natural, but it can retraumatize a person by forcing them to relive the pain. Not everyone is ready to speak openly about searches, torture, or humiliation. It is better to ask: “Do you want to talk about it?” and respect how much they can or wish to share.

7. “I would never be able to survive something like that.”

It sounds like a compliment, but it turns the person into a “hero” and isolates them at the same time. They did not want to be a hero — they simply wanted to live.

Example: many Belarusian political prisoners said they feared not prison itself, but that outside they were seen only as symbols, not as people with pain, needs, imperfections, or even mistakes made behind bars. For accuracy, this is more common in women than in men.

8. “You are completely different now.”

This can sound like judgment. Imprisonment always changes a person, but it is important to accept them without evaluation. Instead, one can say: “I see you’ve been through a lot. How do you feel about these changes?”

It is important to know that traumatic experience is most intense in the first days after release. Over time, the anxieties and restrictions of imprisonment become dulled, leaving an overall impression of that period.

9. “You just need to forget all of this.”

Trauma cannot simply be “forgotten” — it must be processed and integrated into life. Such words make a person feel that their pain and experience are unimportant or unwanted.

10. “Why can’t you just move on? Why do you keep talking about prison? It happened, so live your life!”

These phrases ignore reality: after imprisonment, time is needed for adaptation and recovery of both psyche and body. Instead, one can say: “What could help you right now?”

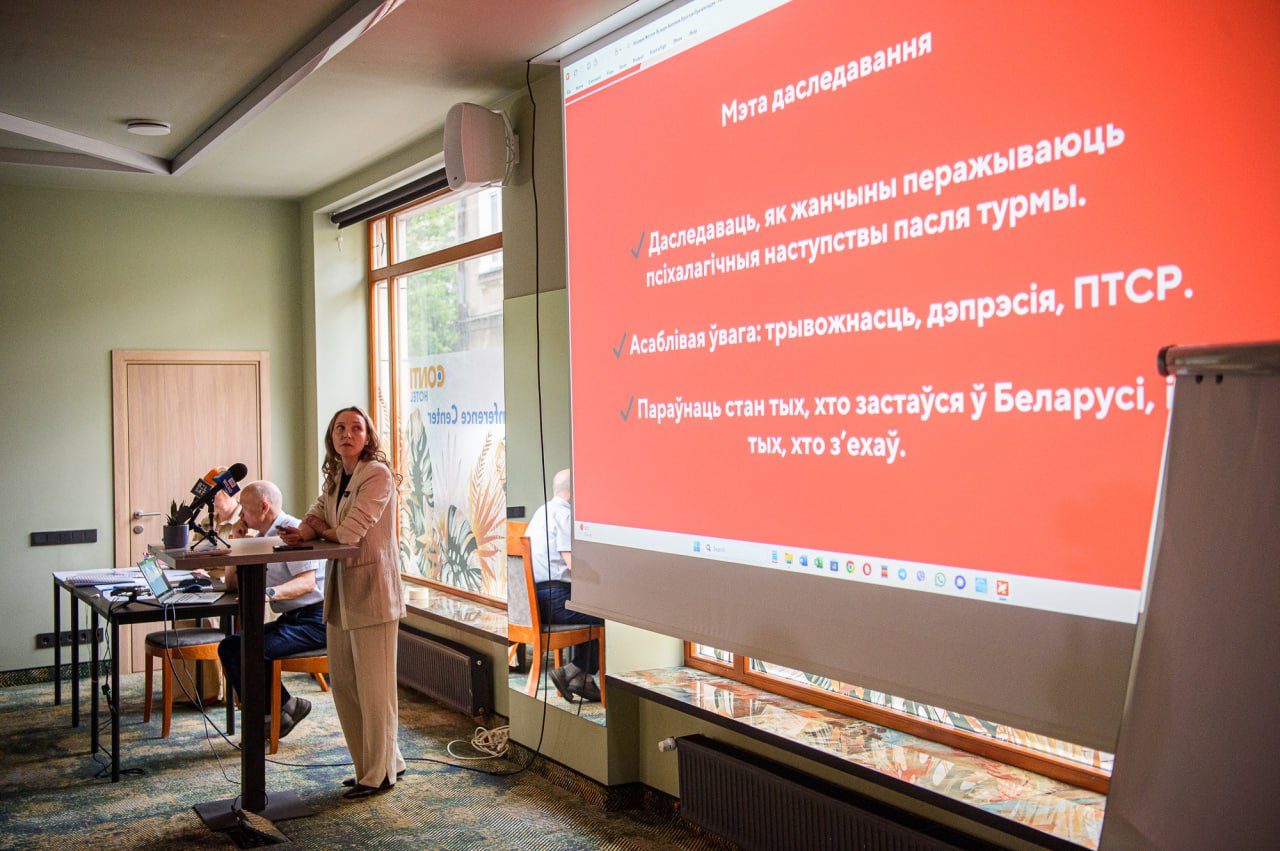

Why is this important?

Such phrases may be said unintentionally, but they can be deeply traumatizing. This applies not only to political prisoners but to everyone who has passed through the system — those convicted in criminal, economic, and other cases. All of them share similar experiences: loss of freedom, fear, adaptation to harsh conditions, and the difficult process of rebuilding life after release.

Machine translation from Belarusian.